Kuwait has deported thousands of migrant workers since launching its unrelenting “security’ campaigns early this year. Undocumented and documented migrants alike have been targeted, detained, and deported with limited means to contest their status. Random, unwarranted, and unregulated raids on workplaces and homes continue to systematically violate migrants’ rights, leaving them traumatized physically and psychologically; one Arab Times article referred to the current predicament of expats as “similar to a scary movie.”

Crackdowns disproportionately and unfairly criminalize both undocumented and documented workers. The lack of regulation has also resulted in the deportation of documented migrants, as police or inspectors can merely claim migrants ‘violated the law.’ For example, a (documented) Indian man who left his house to throw away garbage while still in his “indoor clothes” was arrested and deported. A group of migrants were deported for an “illegal gathering” for attempting to sell their vehicles. Traffic violators have also been deported, though citizens committing similar transgressions are merely fined.

Migrants are uncertain of what crimes invite deportation - traffic violations and the use of VOIP apps may or may not lead to arrest - but regardless, there is scant protection against unfounded detainment or other police misconduct. Though in theory, migrants facing judicial deportation can contest their status, in practice this is often not the case. Deportations by the MOI cannot be challenged.

Furthermore, the inability for migrants to regularize their status or take advantage of an amnesty puts them at risk of exploitation by employers who wield the threat of deportation over their heads. Documented migrants are also at risk as sponsors can extort them by threatening to claim them as absconded.

The ‘deportation regime’ itself embodies state abuse and begets further instances of abuse; in one case, police are accused of raping a documented Filipina woman during a raid. She told reporters:

“I want justice for what they did to me. I will never settle for anything less but for them to be sentenced and sent to prison. I have a valid visa and working decently here in Kuwait. Why did they do this to me?”

In most cases, those violated will not come forward. Abuse is sanctioned and repeatedly defended by vehement state rhetoric. The Ministries of labour and Interior deflect complaints and concerns by condemning the varied opponents of mass deportations - including expatriates, citizens, as well as both local and foreign companies - as “enemies of ministry.”

Kuwait has recently launched aggressive attacks against the welfare of legal migrants as well, including the eviction of migrants renting private residences, the ban on new driving licenses, and reduced health services.

The Interior ministry claims “the laws were applied fairly” and “denies the charge that is targeting expatriates” yet has implemented no measures to ensure the rights of migrants are respected. The MoI also claims there have been no warrantless door-to-door raids, yet Arab Times has received several reports of such illegal incidents.

The ministries fail not only to acknowledge the systematic violations against migrants rights, but also ignore the negative fiscal impacts of mass deportations. Kuwait cannot create more jobs for its citizens by deporting the ‘marginal’ or ‘unskilled’ workers that the MoL claims do not contribute productively to the economy. Aside from the falsehood of these claims (workers must be contributing to the economy if they are in demand in Kuwait), deporting ‘marginal’ workers would not create jobs for Kuwaiti citizens, as citizens are unwilling to take such low-paid, arduous, and socially denigrated positions. Instead, the mass deportations deplete Kuwait of the service and labour workforce that it depends on. The prospective arbitrary deportation of 100,000 foreign workers every year for the next decade can only hinder the Kuwaiti economy:

“Critics of the policy say steep cuts in the foreign workforce are not economically feasible, especially since more labourers will be needed to implement a 30 billion dinar ($108 billion) development plan which includes building a new airport terminal, an oil refinery and hospitals.”

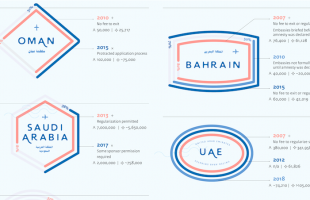

Gulf states that have implemented similar deportation campaigns are already facing the economic consequences; Saudi’s ’Nitiqat’ nationalization scheme has resulted in the cancellation of 36% of its 250,000 registered construction projects as well as an inability to fill 20,000 transportation jobs. Similarly, employment shortages have forced Bahrain to reduce levies on employing foreign workers, which were implemented as part of its own nationalization program.

Migrant rights are systematically sacrificed in the name of poor economics, “security,” and nationalization. Though each state has a right to implement its own immigration policies, it must do so with respect to human rights and in the constraints of relevant international conventions on labour and migration. The severe deportation scheme fails even to address undocumented migration itself, as it only criminalizes migrant workers, failing to address the conditions and other actors that perpetuate irregular migration. Undocumented migration is often not the first choice of migrant workers, but rather the result of fraudulent recruitment agents, unscrupulous sponsors, and illegal visa traders. These issues are endemic to the sponsorship system and to the comprehensive labour policies currently implemented by the Interior and Labour ministries.